Seas and oceans without fish would not just be an ecological crisis. It would also be a major development setback for the millions of people who depend on healthy fisheries for livelihoods and food.

There are plenty more fish in the sea, so goes the old adage.

A decade-long international census of marine life had by 2010 documentednearly 17,000 fish species and estimated that another 5,000 more still remained to be discovered.

That includes everything from enormous whale sharks to the famous clown fish, great schools of mackerel and bottom-dwelling eels.

These all thrive as part of an ecosystem that is home to some 230,000 other marine species in oceans that cover nearly three-quarters of the surface of the planet.

Huge overfishing

The census warned, however, that overfishing and habitat destruction were the main threats to marine biodiversity.

Just over 31% of commercial fish stocks assessed by the UN Food and Agriculture Organization are estimated to be overfished, a figure that has tripled since records began in 1974.

The numbers are worse for some of the ocean’s most valuable fish, with no foreseeable let up.

While some 41% of the main tuna species are currently overfished, market demand remains high, and there is significant overcapacity in the global tuna fishing fleet.

All at sea

Much like climate change, the tale of overfishing is a tragedy of the commons, where, in the absence of property rights over specific fish stock, fishermen may harvest more than the optimal amount for future sustainability.

Fish also do not tend to stay in one place, with many swimming between different national waters – defined as 200 nautical miles from the coast – and into the high seas.

The tragedy then unfolds in various stages, sometimes at the national level where poor fisheries management is manifest, and sometimes in a free-for-all on the high seas, which are not subject to any national or regional oversight.

Government subsidies for fishing have been identified as one significant part of the tragedy.

Distorting subsidies

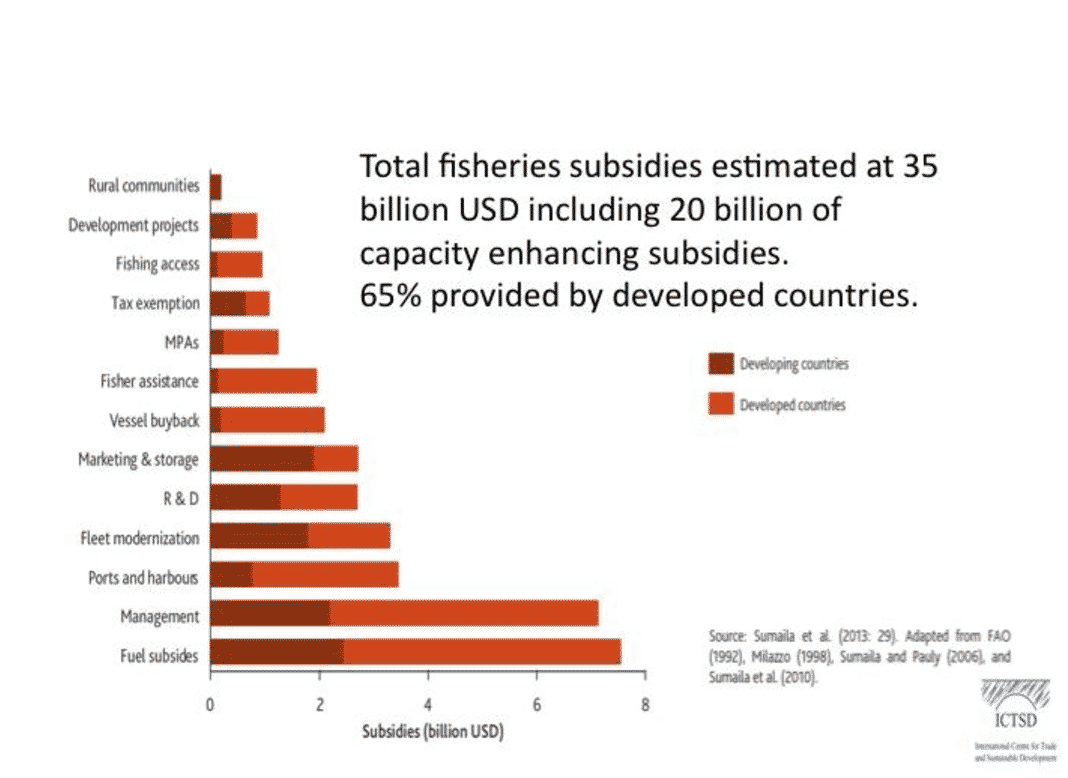

These subsidies come in many forms.

Some may support research and development, others top-up incomes, or provide unemployment insurance.

It is estimated that capacity-enhancing subsidies make up the highest share and amount to around $20 billion. These cover boat construction, tax exemptions, and fuel subsidies, among other things, and can exacerbate overfishing.

Subsidies mean that more boats are built than is necessary, or that fleets stay out longer and roam further into the high seas. Some subsidies even wind up supporting illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing.

Fish as a commodity

Fish are also among the world’s most traded food commodities, and subsidies have an impact on fish prices in global markets.

The World Trade Organization (WTO) has a framework in place to limit the trade-distorting impact of subsidies more generally.

These rules, however, do not take into account negative environmental impacts.

Accordingly, the global trade body launched negotiations in 2001 to reduce fisheries subsidies. To the dismay of advocates of subsidies reform, these talks dragged on and on.

Renewed efforts

Before writing the WTO off, though, the good news is that the topic is firmly back on the agenda and serious efforts are underway, with influential coalitions of countries calling for measures to urgently address this concern.

There is a narrow window of opportunity for governments to seriously engage in talks to bring a deal on fisheries subsidies over the line; but it will not stay open for long.

In 2015, world leaders pledged to prohibit or eliminate certain forms of fisheries subsidies – including those that contribute to overcapacity, overfishing, and IUU – through the global trade body by 2020, as an important contribution to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Time for action

Any world leader with a diary to hand will recognise that it’s time to act in order to stick to this pledge.

This week’s Ocean Conference in New York should focus political attention on getting a deal on fisheries subsidies at the WTO agreed.

The biennial Ministerial Conference of the WTO to be held in December this year in Buenos Aires, presents an immediate opportunity to clinch such a deal.

Political will and a timely thrust to the negotiation process in Geneva may well make all the difference and see the WTO deliver on a really critical matter for the planet.

Hammering out the details will not be easy.

This much we have learned in 16 years of watching talks falter over the definition of fisheries subsidies, respective levels of commitments, and so on.

Breakthrough

A significant breakthrough was made in October 2015 with the conclusion of the regional Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) trade deal that included the first ever rules on reducing fisheries subsidies in any international trade agreement. But that deal, unfortunately, remains on stand-by.

Countries have a number of options to turn progress up to now into a more comprehensive and significant effort, as suggested by a group of leading experts through the E15Initiative research and dialogue process, co-convened by my institution ICTSD, and the World Economic Forum.

So often in the world of international negotiations, however, compromises come at the last minute.

While this is the nature of the game, time is up for many fish species.

Seas and oceans without plenty of fish would be sad indeed, an ecological crisis, and a major development setback for the millions of people who depend on healthy fisheries for livelihoods and food